Many think of augmented reality as recent technology, but there have been iterations of it since the early 1900s. From the sword of Manocles (more on this later) to an app that features users vomiting rainbows, this story is not linear. But it is pretty interesting. So come along as we unpack the fits and starts that make up the history of augmented reality. Let’s go.

In the Beginning, There was AR-ish

Once upon a time in 1901, L. Frank Baum, beloved author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, referenced something AR-like in his novel, The Master Key. He used the term “Character Marker” to describe a set of special glasses. These glasses could project a key onto the foreheads of others. The wearer could tell from a single letter whether someone was good (G), evil (E), wise (W), foolish (F), kind (K), or cruel (C). “Thus you may determine by a single look the true natures of all those you encounter.”

An “electrical fairy tale” it was, though we’re not holding out for character revelations via AR. Afterall, augmented reality isn’t magic, just magical.

It only took 54 more years for something close to augmented reality to appear again, this time as more than an abstract idea. In 1955, Morton Heilig wrote a paper outlining a “Sensorama Simulator” machine concept. Convinced that the theater could and should be multi-sensory, Heilig proposed what he called “Experience Theater”. While not exactly a turning point in the history of augmented reality, the machine provided a 4D experience.

In 1962, a prototype of the Sensorama with sounds, smells, user chair movement, and 3D visuals was built. The machine was not interactive, but it was comprehensive. It came with 5 short films, mostly ride-based experiences. One that seemed to resonate more with investors featured a New York belly dancer. Particular about details, Heilig programmed the machine to spray cheap perfume every time the dancer approached the camera. Ahead of his time, Heilig thought the machine ideal for use in arcades or car showrooms. Perhaps not surprisingly, he was unable to secure funding, and the machine stayed in the prototype stage. This prototype still exists and functions today, though regrettably, it is not available for individual audience use.

Fantastic to Functional

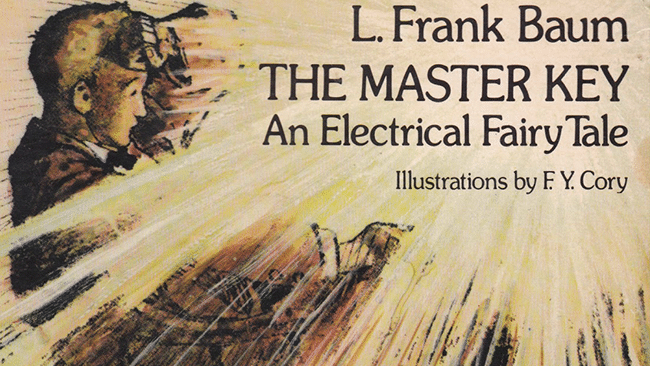

Just 6 years later in 1968, Ivan Sutherland produced the first ever AR headset, sort of. He built the system using computer-generated graphics to show users grid-like rooms. The device was early-stage with primitive wireframes and heavy hardware. Sutherland dubbed it “The Sword of Damocles” based on the necessary mechanical arm tethering it to the wall.

Side note: Damocles, according to legend, was a flatterer in 4th-century Syracuse. In order to teach him a lesson on the perils of happiness, his tyrant king seated him at his throne, surrounded by luxury, but with a massive sword suspended overhead, held only by a single hair. Damocles learned his lesson, begging for removal from the magnificent throne ASAP.

Back to present day, Sutherland’s creation was not truly AR or VR. It was partially see-through, so users were immersed but not entirely. Consequently, the device is often cited as both the first AR and first VR headset ever built. For this and several other inventions, many consider Sutherland the father of computer graphics. In 1988, he won the prestigious Turing Award for Sketchpad, a program that revolutionized our understanding of human-computer interaction. Sutherland continues to innovate today, currently leading the research in Asynchronous Systems at Portland State University.

AR made its way to the small screen in 1981 via a Milwaukee weather report. Inventor and entrepreneur, Dan Reitan developed the first application of augmented reality for television broadcast, forever changing the way we visualize the weather. This new development involved RADAR data situated over a TV image à la partly cloudy with a chance of rain.

This technology was more than just an overlay, mixing real-time images from multiple radar systems and satellites simultaneously. Today graphics include full-motion video image captures, but the original premise is still in use. Following the weather, sports has been quick to adapt AR as a way to enhance broadcasts. In fact, we’re so used to seeing weather visualizations today, that most viewers probably don’t associate them with augmented reality.

Not one for just 15 minutes of fame, Dan Reitan is still hard at work, with multiple patents, inventions and awards to his name.

But First, Infrastructure

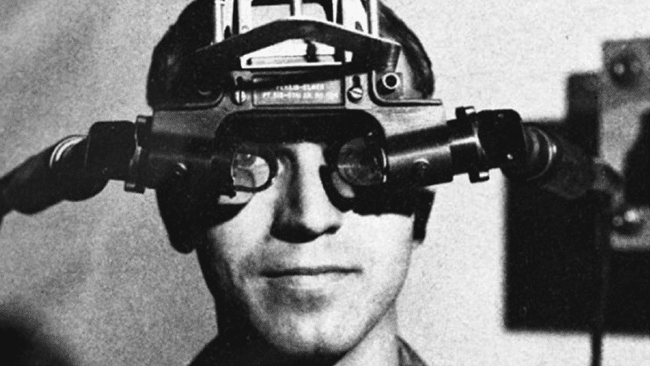

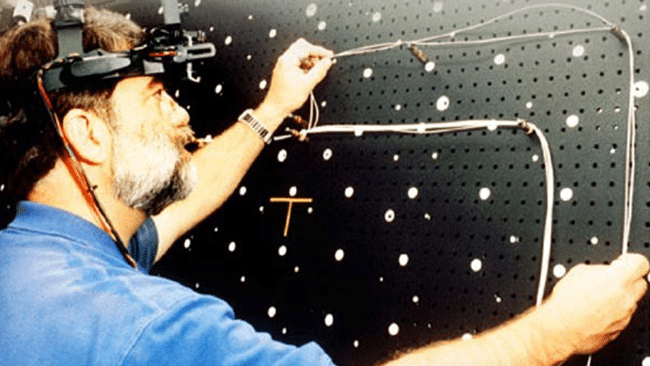

While AR technology continued to evolve, it wasn’t until 1990 that Boeing researcher Tom Caudell coined the term “Augmented Reality”. Up until this point, there was no agreed-upon name for AR. To be fair, it wasn’t really a topic in colloquial conversation. Caudell, however, had a problem that needed an augmented solution. In order to simplify the complicated process of assembling the wiring for a 777 jetliner, augmented reality was born… again.

To better understand, let’s first talk about how things were. Employees were given a sheet with a detailed assembly diagram. While referencing this sheet, an employee would thread and bundle wires along pegs on a 20-30 foot board. In other words, employees were glancing back and forth and back and forth and back and forth between instructions and an incredibly technical process. Not easy.

Caudell and his colleague, David Mizell, were working to find a more efficient alternative when they landed on a head-mounted device. Through an eyepiece, the device displayed each plane’s specific wiring schematics onto multipurpose, reusable materials. This made assembly exponentially easier reducing production time across the board, affecting not just the history of augmented reality, but Boeing as well.

While solving problems left and right, augmented reality and its practical applications were still largely under wraps. For AR to make its way into everyday use, some technological advances were in order. On the hardware side, memory chips and cameras were evolving. In terms of software, ARToolKit was about to make its appearance. In 1999, the first open-source AR software library was created by Hirokazu Kato of Nara Institute of Science and Technology. The University of Washington Human Interface Technology (HIT) Lab later released it to the public. The library, as you probably surmised based on its name and the topic of this post, was comprised of augmented reality components.

This library is still in use today, hosted on GitHub, with over 160,000 downloads on its last public release since 2004. The significance of an open-source software library is the availability of information via peer production and collaboration. Proprietary information is usually shielded from the public and kept for private use. Open-source projects, however, advance technology and promote learning. The same applies to ARToolKit. Acquired by Daqri in 2015, the company re-released ARToolKit, again open-source, in May the same year.

This story is not over, but we are at the end of this post. Check out Part 2 of the history of augmented reality where we dive into the events that made AR a public phenomenon and shaped the way we use and view it today.

Looking for more? Fill your time by taking a learning more about augmented reality in-app vs on the web.

Not a current customer but ready to get started?

Demo the Platform Today!Already a current customer? Log in to Axis Today!